Svalbard: A white and wild ski touring paradise where the polar bear is king

While most of my vacations begin with an examination of a map, this trip begins with a dream‑- a dream that I’ve had since I was a little kid watching All Sails Up, and when I imagined myself on a catamaran expedition to the Polar Regions to meet the penguins, walruses, polar bears and Eskimos.

The dream starts to take form five years ago when I begin skiing with a split-board, a snowboard that can be separated into two pieces similar to skis. During this period, I meet a Swiss man who speaks to me about his project to navigate a small sailboat in the Norwegian fjords. Though the project is eventually cancelled for financial reasons, it fuels my polar dream.

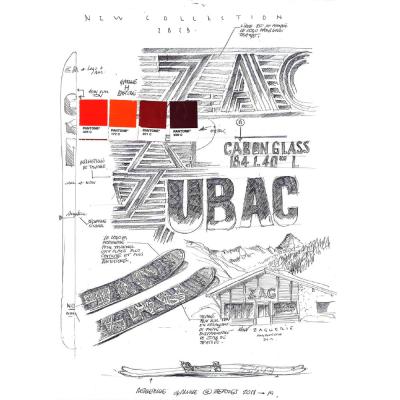

In the meantime, I begin to work with the Swiss Alpine Club and my dear friends, Dinu and Marlene Mititeanu. In 2017, I meet Olivier, a Swiss engineer, world traveller, and ski lover. Together, we create a trip plan that resolves the financial problems, complete with flight details, boat plans, and hotel reservations. ZAG, a ski brand based in Chamonix, France, sponsors me by providing two pairs of light touring skis (from UBAC and ADRET ranges). I bought the rest of the equipment with my own funds and we were ready to begin the adventure.

On April 26th, we leave from the airport in Geneva, have layover in Oslo, and then 15 hours later we land in the tiny Longyearbyen Airport in Spitzberg, an island with a larger area than Switzerland. Spitzberg is part of Svalbard, an archipelago of islands in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, 650 km from Norway and 1000 km from the North Pole. Placed under Norwegian control in 1920, Spitzberg began to open up to tourists at the beginning of the 21st Century thanks to the beautiful animal that can be encountered here, the ursus maritimus, otherwise known as the polar bear. We leave the airport to take the bus to the capital city of Longyearbyen, the most northern city in the world with a permanent civilian population of 3,000. During this time of the year, when spring is just arriving, the sun never sets. This left us 24/24 hours each day to ski, unless the cold was too much.

Once hunted and today protected, the polar bear is the king of the region. This is the first thing that we learn during our security briefing with Andrea Fusari, our Italian guide who insists on the fact that “the bear is in his home, and we are simply guests.” According to the guides who have already encountered the bears, the first thing to do in case of meeting one of these beautiful but dangerous creatures is to make a circle and make as much noise as possible. If the noise isn’t enough to scare the animal, the guides first fire warning shots, and then aim true. Of course, they never target to kill.

On Friday, April 27, the Dutch yacht Vanatu, named after the famous Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn, leaves the Longyearbyen Port with 30 people aboard. Among us, several Swiss passengers, five Germans, two French, two Dutch, a Canadian, and myself (a Romanian exiled in Switzerland).

Our boat, the yacht Rembrandt van Rijn, is equipped with a hull specially reinforced to navigate in the Arctic Ocean. Our first destination is a small fjord called Ymerbukta that we will reach within eight hours of navigation. Life aboard a yacht is not easy. On top of seasickness and bone-chilling cold, we are forced to follow strict rules. Procedures in case of fire, use of special neoprene wet suits, use of emergency life jackets, and procedures for applications of emergency beacons are explained to us each time we board the ship.

Ymerbukta - Physical & ski level tests

At 9:00 AM, we approach the fjord. The lifeboats are on the water. Andrea and Maximo, our two Italian guides, secure the area. The first thing that Andrea does is to load his gun, and then he patrols until all the skiers arrive on the coast. When the second lifeboat prepares to approach, Camile, one of the guides helping passengers disembark, disappears under the ice! The sea ice was not thick enough to bear his weight. We help him get out, but the poor man’s clothes are frozen and his ski boots are full of water. He returns to the yacht to change his clothes, and after 30 minutes, we begin the DVA (Avalanche beacon) search.

Next, we put on our skis in preparation for day’s goal of a small 800-meter summit. Even if the mountains aren’t very high, they are very steep with faces steeper than 40 degrees. Combined with the glaciers, the environment in which we find ourselves quickly becomes quite technical and requires good mountaineering equipment, and of course an excellent skiing ability. Our guides want to get to know everyone’s level in order to create appropriate groups and to determine the calendar for the coming days.

The cloud-cover descends to 300 meters and it will likely remain at this altitude for the rest of the day. We arrange ourselves in a single file line behind Camile, today’s guide. Upon arrival at the summit, we can see next to nothing. We immediately removed our climbing skins, put on our ski boots, and begin our descent. After 5 minutes, when we exit the fog, we realize that we have ended up in the glacier valley and that it now will be impossible to reach the yacht. Andrea calls us over the radio and tells us to bypass the glacier zone and asks to meet us where we had initially approached the shore. When we reach our meeting point, Andrea needs to know everyone’s ski level and physical capacity, so he discretely proposes doing a second summit (600 m) with a time limit of 1.5 hours so we can reach the boat in time to go to another fjord. The rhythm is intense. We have to be careful at each curve, or else we risk tumbling down the slope to take a 1°C bath in the Arctic Ocean. Despite the required prudence, we reach the point where we must to leave our bags and skis and take the last 50 meters on foot.

At this moment, we hear the voice of the captain over Andrea’s radio asking us to return aboard the ship in 30 minutes because a weather front with a lot of wind is coming towards our current fjord. We have one hour to get out of there. We climb the steep frozen slope one after the other. I am last for the descent because Andrea decides I am most experienced with mountainous environments, and thus decides to leave me to handle the back of the group. Unfortunately, the snow layer covering the cliffs isn’t thick enough to allow my skis to glide through the valley. On one turn, my right ski catches corner of a rock, and a few seconds later I find myself taking tight slalom turns through rocks on just one ski. Luckily, my ski brakes snap into function and my loose ski comes to a stop. After a difficult descent, I join the group who is waiting for me below. The result: I pass the ski test and I find myself in a leadership role with the guides, despite the large hole in my ski.

St JonsFjorden arrival

It’s one of those days that you dream about. The weather is excellent, there is no wind, and in front of us peaks seem to rise out of the ocean, ready to welcome us. The night before, several centimeters of fresh snow had fallen. Our group’s guide today is Maximo, the chief guide. After our landing on shore, the plan is to follow an iceberg for several hours and then climb a pyramid shaped summit. After four hours of skiing, we attain the peak. We all feel like children, pulling out our cameras, yelling with joy. It is the paradise that all skiers dream about. At our feet is the beauty of the vast Arctic Ocean. We prepare our skis, and all together, we descend the steep slope heading towards our meeting point, where in our joy we all link arms as if we have known each other forever.

KongsFjorden - Frozen Frog

The third day begins with an early awakening. Our current fjord has an enormous glacier at its base, surrounded by numerous icebergs. The landscape is sublime. The weather seems as if it is about to change, with thick clouds looming on the horizon. The teams had left the base of the glacier, which we manage to get around passing by the right side. As we climb, the slope becomes increasingly steep, and we notice that the force of the wind has sculpted the ridges in sharp points, like lances. Maximo expresses concern at the possibility of slipping along the steep and sharp wall. Once we reach the summit, the sky is already covered. For the descent, we choose a chute with fewer rocks. Maximo goes down first, asking us to wait until he has verified that the snow is stable when he will call us to follow. After 3 minutes, he has already disappeared into the thick layer of clouds, and we hear him call in pure Italian “Dai! Dai!” (Go! Go!). We stay in Kongsgjorden for two days. The next day, because the weather is so bad in the morning, we start skiing at the beginning of the night.

After all, who said we couldn’t ski at night? The sun never sets, and we can ski 24/7 if we really want to.

No one is allowed to be more than 50 meters away from the rest of the group, and the guides are still skiing with guns on their shoulders, ready to react at the slightest sign of alarm. Unfortunately (or fortunately), the only animals that I see are reindeer, polar foxes, seals, and a colony of penguins.

Prins Karl Forland

In the evening, the captain proposes stopping in a small scientific research village, Ny Alesund. Here, the rules are very strict. It’s prohibited to use our telephones or anything that emits or receives a signal. We quickly understand why: along the hills around the village, there are enormous satellite dishes that listen to messages sent from space. The seasonal population of the village is about 100, and is comprised of mostly Russian, Norwegian, and English researchers. In the center of the colony, dotted with colored houses, is an immense Nordpol hotellet (North Pole hotel), and a statue of Roald Amudsen, the first Norwegian to arrive in the North Pole in 1926. There is also a store open from 8:00-9:30 PM where you can buy souvenirs.

I wanted a souvenir, so I asked them to stamp my passport. This stamp is the most beautiful souvenir one could ask for in Ny Alesund, and it helps me remember the city of the 79th Meridian each time I open my passport. In this city, the farthest north in the world, I spot a Russian iceboat and submarine from afar, monstrous machines traversing the frozen waters.

The next day on Prins Karl Forland, a parallel island to Spitzberg, I enjoy a magnificent ski day under the light of a mythical sunset. The ice, which surrounds us completely, resembles emerald. I feel like we are prisoners (this feeling will later become reality when I see the yacht surrounded by the ice bank). Without great surprise, we discover that we can no longer exit from the point where we entered because the ice had surrounded us in less than 10 minutes.

The return to Longyearbyen does not go smoothly. The first incident is immediately after our goodbye dinner, when the boat begins to sway and swing from the wind. Everyone aboard except the crew begins to feel sick. While the others exit to the bridge to empty their stomachs, I preferred to stay in the cabin and sleep. About midway through the journey, I awaken to hear loud noises that resemble a herd of charging rams. Afraid, I quickly head to the bridge to see what is going on. I am surprised to realize that we are traversing a zone full of ice fragments, some much larger than others. I can’t sleep until we arrive at Longyearbuyen Port where we board a bus at 2:00 AM to leave the port. 2.5 hours later, after the plane had been de-iced and after a long time waiting at the small airport’s frozen runway, we begin our Oslo-Copenhagen-Geneva return journey.

Now, I can say that my childhood dream became reality. I am already dreaming about next year.

Text/Images: Florin Bîscu